PITTSBURGH (AP) — For over 20 years, the work of gospel music composer Charles Henry Pace sat in 14 unorganized crates, dirty and decomposing. This was until a music historian at the University of Pittsburgh was inspired to uncover the true history behind the photo negatives, printing plates and pieces of sheet music the university acquired in 1999. As a result, they’ve discovered that Pace was an early pioneer of gospel music whose independently owned publishing company helped elevate and expand the genre. This week the community will honor Pace and his wife Frankie with a free concert in the historic Hill District of Pittsburgh, showcasing some of his work.

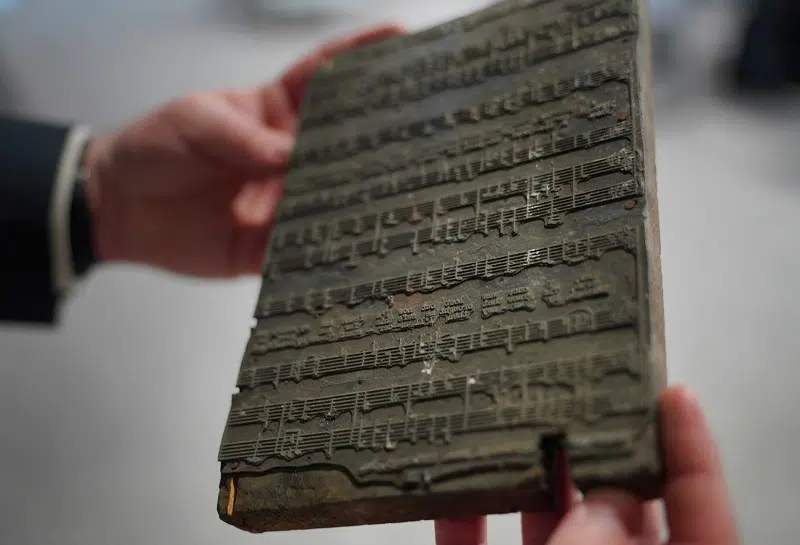

Christopher Lynch, music historian and project coordinator with the Center for American Music at the University of Pittsburgh, holds a printing plate that gospel composer and publisher Charles Henry Pace used to print sheet music, on Tuesday, Feb. 28, 2023, at the University of Pittsburgh, in Pittsburgh. The plate is part of a larger archive owned and housed by the university. (AP Photo/Jessie Wardarski)

Extended version:

PITTSBURGH (AP) — Scattered in crates, dirty and difficult to read, the gospel music of composer Charles Henry Pace sat packed away, unorganized — and unrealized — for more than 20 years.

Frances Pace Barnes, the pioneering music publisher’s daughter who remembers how he could turn a hum into a song, knew the crates held pieces of her family’s past. But she was not expecting those decaying printing plates and papers to reveal an important part of gospel music history.

“I didn’t know it was going to be a legacy,” said Pace Barnes.

As it turns out, her father was one of the first African American gospel music composers in the United States, and the owner of one of the country’s first independent, Black gospel music publishing companies.

Today, the University of Pittsburgh is restoring his work from the 1920s to the 1950s and cementing his place in the genre’s history. It was the curiosity of music historian Christopher Lynch that set the Charles Henry Pace preservation project into motion.

“This is something that we can, as Pittsburghers, all be proud of,” said Lynch with a smile. “Charles Pace was a tremendous figure in music history.”

Long after Pace died in 1963, his music store, which was first known as the Old Ship of Zion and later changed to the Charles H. Pace Music Publishers located in Pittsburgh’s Hill District, was sold and his archives went with it. Eventually, the materials made their way to auction, and the university’s library system bought them in 1999.

The 14 crates sat for more than two decades before Lynch, who also is the project’s coordinator with the university’s Center for American Music, uncovered the significance of what they held.

Lynch, who moved to Pittsburgh in 2017, was inspired to go through them after taking a tour of the Hill District — the city’s first hub of Black culture and art — and learning that a park in the area would be dedicated to Pace’s wife and community activist, Frankie Pace.

But his task was large. And in 2021 he began organizing, cleaning and deciphering the 250 printing plates and about 600 photographs that detailed Pace’s legacy.

“I quickly realized that ‘Oh, we had something here,’” said Lynch.

Although the genre’s roots reach as far back as 19th century spiritual songs, the lineage of modern gospel music heard in Black churches today includes the work of musicians and composers who emerged in the 1920s.

Those pioneers include Thomas Dorsey, who is often called the father of gospel music, “giving the impression that he pretty much singlehandedly invented this style,” said Lynch.

But after digging into Pace’s early work, he says it was around the same time, or even a few years before Dorsey. This has helped the historians piece together the community of musicians who pushed gospel music forward as it began entering popular culture.

During this period, African American gospel music composers didn’t have access to large publishing companies so Pace learned to do it all himself. Lynch says an important part of the archival work is restoring the true history and giving credit where credit is due since many of Pace’s most recorded songs, including, “If I Be Lifted Up,” are rarely credited to him, listed instead as “traditional songs.”

Pace got his start in Chicago, creating his first publishing company where he worked on the early music of Dorsey. He also formed the Pace Jubilee Singers, which was one of the first Black groups to record gospel music and perform on the radio. Soon after meeting his wife, the couple relocated on Pittsburgh’s North Side where Pace introduced gospel music in 1936 to Tabernacle Baptist Church as the music director and later opened their store in the Hill District.

The couple formed the Pace Choral Union, a gospel choir of 75 singers at its inception and 200 at its peak. They helped establish gospel music across the city, performing at churches and events throughout Pittsburgh and western Pennsylvania as well as weekly on the radio.

“I really didn’t realize until I was much older how talented my father was,” said Pace Barnes, who grew up working in his store.

The storefront, which doubled as an office, sold gospel music and church literature. Artists, unable to write their own music, could come to Pace with an idea. He would arrange it, and then, print and publish the songs.

The storefront became a hub for some big name, traveling musicians like Louis Armstrong and W. C. Handy.

Pace was one of few people who knew how to fully print sheet music using photo negatives and metal plates mounted onto scrap wood. This was crucial to the expansion of gospel music in the U.S.

“To think he was doing this basically in the back of a shop or in his house in the thirties, in the forties…” said Pace’s grandson Frank Barnes in awe.

Frankie and Charles were also able to build a wide-ranging geographical distribution network of 301 stores across 29 different states. They also had a consistent list of more than 2510 mail subscribers who ordered from him directly.

“He’s one of the early evangelists of gospel music,” said Kimberly Ellis, an American historian and founding executive director of the Historic Hill Institute, who is currently working on an oral history project on Frankie Pace. “It meant that he literally spread the good news, via music, from coast to coast. Which is amazing.”

In addition to co-owning the music store and singing in the Pace Gospel Choral Union, Frankie Pace earned a reputation as a strong community activist. She worked with various groups to improve education and housing conditions, and co-founded a committee that advocated for mandatory community input on any future development in the Hill District.

Thrilled that Charles Pace will be placed in his proper context, Ellis also hopes that bringing this music to light will help “transform what we know about history.”

The work has transformed what Pace’s grandson now knows about his family history. He grew up in Chicago knowing little about his grandfather, who died six years before he was born. Worried about making his mother sad, he often resisted the urge to ask questions about him.

“Things can so easily get lost,” he said. “Whether it be artifacts like the plates, or whether it be the stories of the people in their trajectory, like my grandparents.”

Barnes and his mother are glad the Pace archives will remain at the university, giving future generations the opportunity to learn about their patriarch. More immediately, the city will honor the legacies of Charles and Frankie Pace on Saturday with a free concert showcasing music composed by Pace and the rededication of Frankie Mae Pace Park.

“This is history, and we are part of making history again,” said director and founder of The Heritage Gospel Chorale of Pittsburgh, Herbert V.R.P. Jones, who will be one of the main performers that evening.

Francis Pace Barnes, who hasn’t been to Pittsburgh since her mother died in 1989, will be there with her son, listening to her father’s music in the church where he once worked.

“I’m looking forward to hearing songs I haven’t heard in 40 years,” she said.

Comments