July 9, 2025:

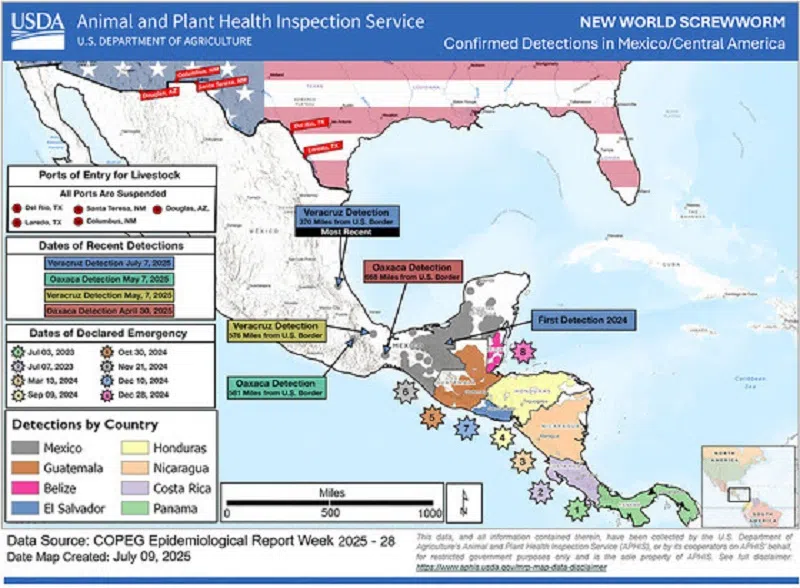

Tuesday (July 8, 2025), Mexico’s National Service of Agro-Alimentary Health, Safety, and Quality (SENASICA) reported a new case of New World Screwworm (NWS) in Ixhuatlan de Madero, Veracruz in Mexico, which is approximately 160 miles northward of the current sterile fly dispersal grid, on the eastern side of the country and 370 miles south of the U.S./Mexico border. This new northward detection comes approximately two months after northern detections were reported in Oaxaca and Veracruz, less than 700 miles away from the U.S. border, which triggered the closure of our ports to Mexican cattle, bison, and horses on May 11, 2025.

While USDA announced a risk-based phased port re-opening strategy for cattle, bison, and equine from Mexico beginning as early as July 7, 2025, this newly reported NWS case raises significant concern about the previously reported information shared by Mexican officials and severely compromises the outlined port reopening schedule of five ports from July 7-September 15. Therefore, in order to protect American livestock and our nation’s food supply, Secretary Rollins has ordered the closure of livestock trade through southern ports of entry effective immediately.

“The United States has promised to be vigilant — and after detecting this new NWS case, we are pausing the planned port reopening’s to further quarantine and target this deadly pest in Mexico. We must see additional progress combatting NWS in Veracruz and other nearby Mexican states in order to reopen livestock ports along the Southern border,” said U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Brooke L. Rollins. “Thanks to the aggressive monitoring by USDA staff in the U.S. and in Mexico, we have been able to take quick and decisive action to respond to the spread of this deadly pest.”

To ensure the protection of U.S. livestock herds, USDA is holding Mexico accountable by ensuring proactive measures are being taken to maintain a NWS free barrier. This is maintained with stringent animal movement controls, surveillance, trapping, and following the proven science to push the NWS barrier south in phases as quickly as possible.

In June, Secretary Rollins launched a Bold Plan to combat New World Screwworm by protecting our border at all costs, increasing eradication efforts in Mexico, and increasing readiness. USDA also announced the groundbreaking of a sterile fly dispersal facility in South Texas. This facility will provide a critical contingency capability to disperse sterile flies should a NWS detection be made in the southern United States. Simultaneously, USDA is moving forward with the design process to build a domestic sterile fly production facility to ensure it has the resources to push NWS back to the Darien Gap. USDA is working on these efforts in lockstep with border states – Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas – as it will take a coordinated approach with federal, state, and local partners to keep this pest at bay and out of the U.S.

USDA will continue to have personnel perform site visits throughout Mexico to ensure the Mexican government has adequate protocols and surveillance in place to combat this pest effectively and efficiently.

July 8, 2025:

The Mexican government has started construction on a $51 million facility in southern Mexico as part of an effort to combat the New World screwworm that’s disrupted Mexican cattle exports to the U.S.

Mexico’s agriculture ministry said the plant is a joint project with the U.S. and will produce 100 million sterile screwworm flies per week once completed in the first half of next year. The release of sterile flies reduces the population of wild flies and is a key tool in helping to control the damaging pest. Mexico is paying $30 million of the cost and the U.S. is spending $21 million. The U.S. also has plans to open a sterile fly dispersal facility in Texas as part of the ongoing battle against screwworm. The pest carries maggots that burrow into the skin of living animals, causing serious and often fatal damage.

May 27, 2025:

U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Brooke L. Rollins provided an update on the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) ongoing partnership with Mexico to combat the New World Screwworm (NWS). Tuesday (May 27, 2025), Secretary Rollins held a call with her counterpart in Mexico, Secretary Berdegue, to discuss the ongoing threat of NWS and actions being taken by both countries to contain the threat south of the U.S. border. USDA is working daily with Mexico to make sure the resources, tactics, and tools are in place to effectively eradicate NWS. Additionally, Secretary Rollins announced today the USDA is investing $21 million to renovate an existing fruit fly production facility in Metapa, Mexico to further the long-term goal of eradicating this insect. When operational, this facility will produce 60-100 million additional sterile NWS flies weekly to push the population further south in Mexico. Given the geographic spread of NWS, this additional production capacity will be critical to our response.

“Our partnership with Mexico is crucial in making this effort a success,” said Secretary Rollins. “We are continuing to work closely with Mexico to push NWS away from the United States and out of Mexico. The investment I am announcing today is one of many efforts my team is making around the clock to protect our animals, our farm economy, and the security of our nation’s food supply.”

Current restrictions on live animal imports from Mexico remain in place, and as previously announced, USDA will continue to evaluate the current suspension every 30 days.

USDA and its partners have used sterile insect technique, or SIT, along with other strategies such as intense surveillance and import controls for decades to eradicate and effectively keep NWS at bay. Currently, U.S. supported sterile insect rearing and dispersal operations in Mexico and Central America have been operating at full production capacity, with up to 44 flights a week releasing 100 million sterile flies. All flies used today are raised in the Panama – United States Commission for the Eradication and Prevention of Screwworm (COPEG) Facility in Panama. This investment in the Metapa facility in Mexico would allow USDA to double the use of SIT.

Additionally, USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) and its Mexican counterparts continue to hold ongoing technical calls and meetings on NWS. They are making strong progress toward enhancing surveillance in Mexico, addressing administrative or regulatory roadblocks that could impair an effective response, and ensuring appropriate animal movement controls are in place to prevent further NWS spread. The Mexican delegation joined APHIS in DC last week to discuss these efforts, and APHIS will have a technical team visiting Mexico in the coming weeks to assess the on-the-ground situation and continue working toward key goals around surveillance and animal movement.

April 30, 2025:

The U.S. and Mexico reached an agreement on how to handle a damaging livestock pest called New World screwworm.

Reuters says the agreement was reached only after Ag Secretary Brooke Rollins threatened to limit Mexican cattle imports coming through the southern U.S. border. Screwworms can infect livestock, wildlife, and in rare cases, they can infect people. The screwworm flies leave maggots that burrow into the skin of living animals, doing significant and often fatal damage.

Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum said earlier this week that Mexico had been working to respond to the screwworm outbreak and strengthening its prevention efforts. The U.S. typically imports over one million Mexican cattle every year. Blocking Mexican cattle imports would only tighten U.S. supplies that have dropped to their lowest levels in decades. Washington blocked Mexican cattle from late November 2024 to February 2025 after Mexican officials discovered the screwworm, which America eradicated in 1966.

February 1, 2025:

The United States Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service has given the “okay” for cattle and bison imports from Mexico to resume.

To protect U.S. livestock and other animals, APHIS halted shipments of Mexican cattle and bison in November 2024 after a positive detection of New World screwworm (NWS) in southern Mexico. After extensive discussions between representatives from the countries, APHIS and Mexico agreed to and implemented a comprehensive pre-clearance inspection and treatment protocol to ensure safe movement and mitigate the threat of NWS.

APHIS’ top priority is to protect American livestock from foreign pests. As part of the protocol signed between the countries, Mexico identified and prepared pre-export inspection pens in San Jeronimo, Chihuahua, and Agua Prieta, Sonora, which APHIS has now visited, inspected, and approved. Cattle and bison will be inspected and treated for screwworm by trained and authorized veterinarians prior to entering the pre-export inspection pens, where they will again undergo inspection by Mexican officials before proceeding to final APHIS inspection then crossing at the Santa Teresa and Douglas Ports of Entry, respectively. Cattle and bison approved for importation will also be dipped in a solution to ensure they are otherwise insect- and tick -free. The United States and Mexico are working closely to approve additional pre-export inspection pens and reopen trade through other ports of entry.

To support our efforts to keep NWS out of the United States, APHIS will continue working with partners in Mexico and Central America to eradicate NWS from the affected areas and to reestablish the biological barrier in Panama, which we have worked to maintain since 2006.

In the last two years, screwworm has spread north of the barrier throughout Panama and into Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala, El Salvador, Belize and now Mexico. This increase is due to multiple factors including new areas of farming in previous barrier regions for fly control and increased cattle movements into the region. APHIS is releasing sterile flies through aerial and ground release at strategic locations, focusing on Southern Mexico and other areas throughout Central America. A complete list of regions APHIS recognizes as affected by screwworm as well as more detailed information on trade restrictions can be found on the USDA APHIS Animal Health Status of Regions website.

December 14, 2024:

U.S. Senator Mike Rounds (R-S.D.) sent (Dec. 12, 2024) a letter to Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack requesting the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) to thoroughly investigate the threat of the New World Screwworm (NWS) prior to reopening the U.S.-Mexico feeder cattle trade.

On November 24, 2024, USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) decided to halt imports of livestock from Mexico after a detection of NWS in Chiapas, Mexico. This temporary action was taken to prevent further spread to U.S. markets. While NWS was believed to be eradicated from the United States in 1966, a single detection of the parasite within our borders could have significant consequences for U.S. cattle markets.

“To address current threats, I urge the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) to proceed with real caution and to refrain from prematurely reopening the U.S.-Mexico feeder cattle trade,” Rounds wrote. “Prior to reopening this trade, USDA must thoroughly assess and address the concerns of the entire cattle industry. Additionally, animal health officials must effectively investigate the source of this spread.”

Read the full letter HERE or below.

++

Dear Secretary Vilsack,

American ranchers produce the highest quality beef in the world. The high demand for American beef has allowed producers to consistently supply a safe product to consumers across the globe. Yet as you know, foreign disease threats to the beef supply are always prevalent. In the past month, a threat has emerged in the form of the New World Screwworm (NWS).

As you know, NWS has been a persistent issue in the western hemisphere for decades. While the United States worked to eradicate NWS in 1966, the parasite has remained present in certain parts of Central and South America. In partnership with Mexico, U.S. officials have been able to largely contain the parasite. Despite these efforts, NWS detections have occurred periodically. The parasite presents not only a serious threat to animal safety, but it also has the potential to disrupt U.S. cattle markets.

Following a recent detection of NWS in Chiapas, U.S. officials made the right choice to halt feeder cattle imports from Mexico on November 24, 2024. While this action is temporary, it has allowed animal health officials to implement necessary surveillance measures.

To address current threats, I urge the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) to proceed with real caution and to refrain from prematurely reopening the U.S.-Mexico feeder cattle trade. Prior to reopening this trade, USDA must thoroughly assess and address the concerns of the entire cattle industry. Additionally, animal health officials must effectively investigate the source of this spread.

I also encourage APHIS to clearly outline the process for making these trade decisions.

Animal health officials should take all the necessary steps to protect American producers. Our ranchers consistently deal with a number of uncontrollable factors, including rising input costs and volatile markets. It would be irresponsible to subject our domestic cattle herd to further uncertainty.

Thank you for your consideration of these requests.

November 27, 2024:

The United States has paused imports of cattle from Mexico (Nov. 25, 2024) after a positive detection of New World screwworm, a flesh-eating pest that can be fatal to animals and in some cases humans. Authorities identified an infected cow at a livestock inspection checkpoint close to the border of Guatemala. Given the northward movement of screwworm, USDA said it is “restricting the importation of animal commodities,” including live cattle and bison, that originated or were transported through Mexico, effective immediately.

The suspension of Mexican cattle could affect U.S. beef production and prices. The pest, which gets its name from the way it burrows into wounds like a screw, last appeared in Florida in 2016 and marked the first U.S. outbreak in decades. The U.S. has relied on live cattle imports from Canada and Mexico to fill in the gaps from years of herd declines.

Comments